On the way home from school one day, aged nine, a news report on the radio told its listeners, including my Nan and I, that Myra Hindley had been hospitalised. As I listened, I wondered who this woman was, why she was important, and asked my Nan the question that would lead to many a sleepless night; ‘Who is Myra Hindley?’

A nine-year old’s mind is often irrational in its fear of something; some are afraid of ghosts, others of the monster under the bed. I was afraid of Myra Hindley and Ian Brady; the Moors Murderers, whose killing spree in the 1960s terrified me. Did they know where I lived? What if they came to find me? I couldn’t get what they had done out of my head.

In hindsight, my Nan probably shouldn’t have t old a nine-year old about the Moors Murders, and if she had, maybe she should have omitted certain aspects of the story. But from that point onwards, I always wondered why two people had ‘gone so bad’, how they could have committed such atrocious crimes, and why one of them was constantly fighting to be released from prison. I mean, wasn’t she sorry?!

old a nine-year old about the Moors Murders, and if she had, maybe she should have omitted certain aspects of the story. But from that point onwards, I always wondered why two people had ‘gone so bad’, how they could have committed such atrocious crimes, and why one of them was constantly fighting to be released from prison. I mean, wasn’t she sorry?!

The fear lessened as I got older; I knew that the pair of them couldn’t ‘get me’, and in 2002, Myra Hindley died. But I never forgot what they did and how disgusted I felt, and still feel, about their crimes.

But I find that when you’re scared of something, you want to find out more about it. So I did; I watched documentaries and read books on this period in history, to get a better understanding of how two people could be so evil. It’s pretty hard to admit that you’re interested in two serial killers, without being seen as a psycho or a potential serial killer yourself. But I’m not alone, and when Carol Ann Duffy wrote this poem from Myra Hindley’s point of view, I found it really thought-provoking.

I think you need to have a good understanding of Myra Hindley’s life in order to truly understand the references Duffy makes in this poem. But if you do, it’s such an interesting read.

Before Myra Hindley, women were seen as incapable of such a crime. But she ‘gave the camera my Medusa stare’, and from then on, she was portrayed in the media as a heartless monster; a soulless woman, and from my point of view, rightfully so. But she had her supporters too; most notably, ‘her MP’-Lord Longford, whose political views are incredibly amusing in their contradictory nature.

Duffy really gives Myra Hindley a voice in this poem, and it’s pretty chilling stuff. Yes, the devil is evil, but the devil’s wife; how can a woman allow herself to covet such a title?

The Devil’s Wife

1. Dirt

The Devil was one of the men at work,

Different. Fancied himself. Looked at the girls

in the office as though they were dirt. Didn’t flirt.

Didn’t speak. Was sarcastic and rude if he did.

I’d stare him out, chewing on my gum, insolent, dumb.

I’d lie on my bed at home, on fire for him.

I scowled and pouted and sneered. I gave

as good as I got till he asked me out. In his car

He put two fags in his mouth and lit them both.

He bit my breast. His language was foul. He entered me.

We’re the same, he said, That’s it. I swooned in my soul.

We drove to the woods and he made me bury a doll.

I went mad for the sex. I won’t repeat what we did.

We gave up going to work. It was either the woods

or looking at playgrounds, fairgrounds. Coloured lights

in the rain. I’d walk around on my own. He tailed.

I felt like this: Tongue of stone. Two black slates

for eyes. Thumped wound of a mouth. Nobody’s Mam.

2. Medusa

I flew in my chains over the wood where we’d buried

the doll. I know it was me who was there.

I know I carried the spade. I know I was covered in mud.

But I cannot remember how or when or precisely where.

Nobody liked my hair. Nobody liked how I spoke.

He held my heart in his fist and he squeezed it dry.

I gave the cameras my Medusa stare.

I heard the judge summing up. I didn’t care.

I was left to rot. I was locked up, double-locked.

I know they chucked the key. It was nowt to me.

I wrote to him every day in our private code.

I thought in twelve, fifteen, we’d be out on the open road.

But life, they said, means life. Dying inside.

The Devil was evil, mad, but I was the Devil’s wife

which made me worse. I howled in my cell.

If the Devil was gone then how could this be hell?

3. Bible

I said No not me I didn’t I couldn’t I wouldn’t.

Can’t remember no idea not in the room.

Get me a Bible honestly promise you swear.

I never not in a million years it was him.

I said Send me a lawyer a vicar a priest.

Send me a TV crew send me a journalist.

Can’t remember not in the room. Send me

a shrink where’s my MP send him to me.

I said Not fair not right not on not true

not like that. Didn’t see didn’t know didn’t hear.

Maybe this maybe that not sure not certain maybe.

Can’t remember no idea it was him it was him.

Can’t remember no idea not in the room.

No idea can’t remember not in the room.

4. Night

In the long fifty-year night,

these are the words that crawl out of the wall:

Suffer. Monster. Burn in Hell.

When morning comes,

I will finally tell.

Amen.

5. Appeal

If I’d been stoned to death

If I’d been hung by the neck

If I’d been shaved and strapped to the Chair

If an injection

If my peroxide head on the block

If my tongue torn out at the root

If from ear to ear my throat

If a bullet a hammer a knife

If life means life means life means life

But what did I do to us all, to myself

When I was the Devil’s wife?

A Flower Has Opened In My Heart

A Flower Has Opened In My Heart Your clear eye is the one absolutely beautiful thing.

Your clear eye is the one absolutely beautiful thing. old a nine-year old about the

old a nine-year old about the

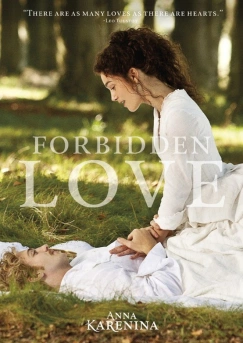

I read Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy over a month ago, yet I still find myself thinking about it even now. It is one of those books that when you close the final page you hold it in your hands, lean back in your chair, and think; ‘Wow’.

I read Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy over a month ago, yet I still find myself thinking about it even now. It is one of those books that when you close the final page you hold it in your hands, lean back in your chair, and think; ‘Wow’.